I conducted a thematic analysis of the thirteen research impact frameworks to develop a framework based on a descriptive view of existing frameworks and systems-thinking approach to each component. In this post, I lay out the framework that consists of three types of research impact: execution, influence, outcome. This framework is intended to be heuristically useful and naturally prescriptive of the value for each type of impact.

Developing the framework

Research impact has been a big topic the past few years as layoffs swept over the field of UX research (disproportionately). The layoffs spurred a wave of perspectives on why UX researchers need to drive business value more clearly, align with company goals, or even re-imagine the practice of research as a seasonal position. Most of these articles posit that researchers need to do better when it comes to achieving and communicating their impact. However, some have argued that researchers are not at fault for their own layoffs (and here).

Personally, I fall in with the latter group: I don’t think researchers as a body of practitioners have failed to act in a certain way, causing all of our layoffs. We don’t operate as a unit and our incentives vary by individual, team, and organization. My goal here is not to talk about the cause for the layoffs (read my citations), but to explain why we care about impact in the first place.

Of the thirteen frameworks I reviewed, only one (LaMar, 2024) explicitly motivated the value of impact explicitly with the layoffs. But I do believe the rapid proliferation of impact frameworks (nine in the last 2 years!) is at least indirectly spurred by the anxiety related to our current hiring/staffing landscape. However, research impact is not simply a survival response to layoffs.

UX research has always been action research, linking research practice with decisions inexorably. In a robust UX research practice, impact will be central after the current layoffs, as it is now, and was before. I’ve been using a research impact tracker years prior to the current hiring turmoil.

In the next sections, I lay out my process to formalizing the general model of research impact I’ve used in my career. The process was guided in principle by three things: descriptively considering all publicly available frameworks, having a systems-thinking approach (how are impact components connected? why?), and being useful for the ways individual researchers need to use impact for their careers.

Defining impact in UX research

I reviewed 13 frameworks about impact in UX research. All of the frameworks I reviewed provided components of impact, and often how to track them. Only some frameworks defined impact, a few others noted the purpose of UX research as a whole, and some did not provide any definitional materials beyond the components themselves.

The purpose of UX research was most often defined in terms of supporting or influencing decision-making, and some linking these decisions to eventual improvements in the product and/or company business goals.

Impact was similarly defined as influencing the product, organization, strategy, or individuals within a business, when it was defined at all. However, looking descriptively at what researchers are defining and tracking as impact, research impact includes the research process and how its results drive decisions and affect stakeholder outcomes.

Despite the breadth of a descriptive view of activities and results related impact, the key theme was clearly “influence”. That influence was sometimes tied to downstream goals (product or business metrics) of other functions in the organization. This led me to my framework which has influence at the center, surrounded by the inputs that lead to influence and the desired downstream outputs from influence.

Reframing impact

Analysis and development

I mapped out all of the components of the thirteen impact frameworks I found into a spreadsheet and thematically analyzed the components (full dataset).

At high level, there is little agreement for how to organize the components of research impact in the thirteen frameworks I reviewed. The terms vary and the number of components also vary. Many do focus on how researchers influence others, but how that is categorized varies significantly. Some heavily feature operational aspects of research1, while others don’t consider this impact at all. Some don’t make any mention of product or business metrics2. Ultimately, the variation present makes sense given that each organization has unique needs and will want to measure impact differently3.

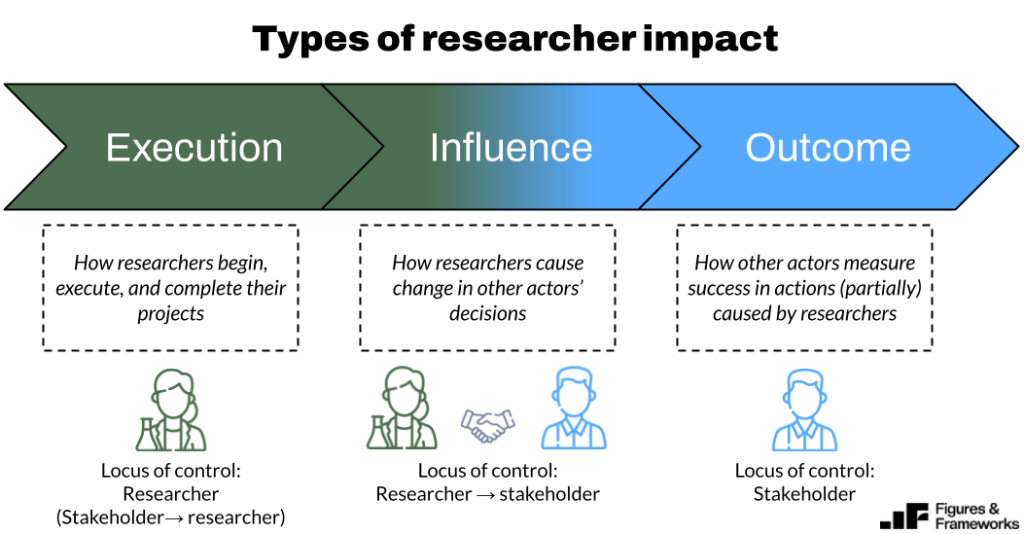

Still, a theme emerged when looking at the locus of control across actors in an organization. In plain terms, who owns the steps, or where does ownership change? This is the researcher-centric view my framework builds on (locus of control was first referenced by Dong, 2021).

Here are my three components of the researcher-centric impact framework:

- Execution: How researchers begin, execute, and complete their projects

- Influence: How researchers cause change in other actors and systems in the organization

- Outcome: How other actors measure success in actions (partially) influenced by researchers

My framework does have some similarities with other frameworks. In particular, the components overlap significantly with Dong (2021), likely due to his emphasis on the locus on control. The components also aligns closely with Shukla (2021) and den Bouwmeester’s revised version and original version (2025, 2023). LaMar (2024) does not focus on execution, but his human impact and product impact metrics fit within my influence category, and business impact aligns with my outcome component. Other frameworks have far more numerous components or do not include stakeholder outcomes.

What the framework does and doesn’t aim to be

The resulting impact framework is researcher-centric, which isn’t a claim that companies are researcher-centric, but researcher’s self-reflective stories certainly are. It’s not attempting to be the truest or most accurate in a purely objective way.

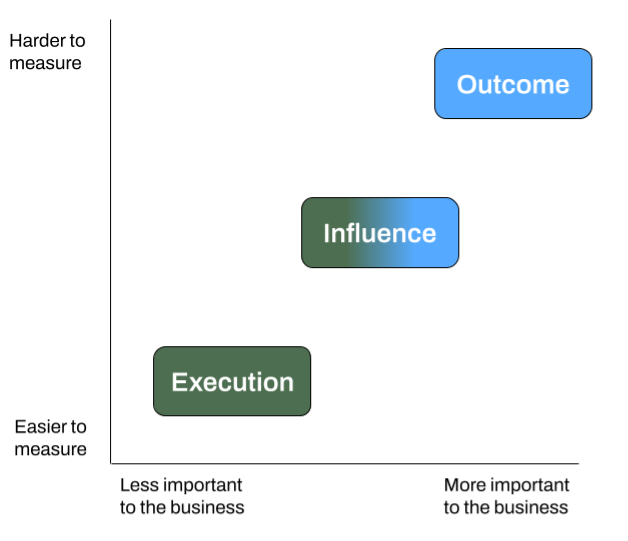

I did aim for this to be a highly useful framework. It correlates nicely along a few different axes such as importance to the business and ease of measurement for researchers (see table). These factors lead to a prescription of what researchers should focus on for their impact when executing their work, tracking impact, or writing an impact statement (post to come soon about writing an impact statement).

This framework is not a template for what metrics to use, so I avoid sharing those here except to show what a component is by example. In fact, I will argue in another post (coming soon) that over-indexing on impact metrics/measures ignores the qualitative nature of impact itself. If you are curious about specific metrics for impact, I’d dig into the citations, especially Pryor (2024), den Bouwmeester (2023), and Dombrowski & Whitman (2024).

This framework does also not tackle scale as an orthogonal concept to impact components. I’d suggest digging into Sosik (2024) and recent work by Dave Hora to unpack more on scale.

Components of research impact

I’ve given the quick definition of each component of impact, now let’s do a deeper dive in each. I’ll reference some examples to help make these more concrete.

Execution

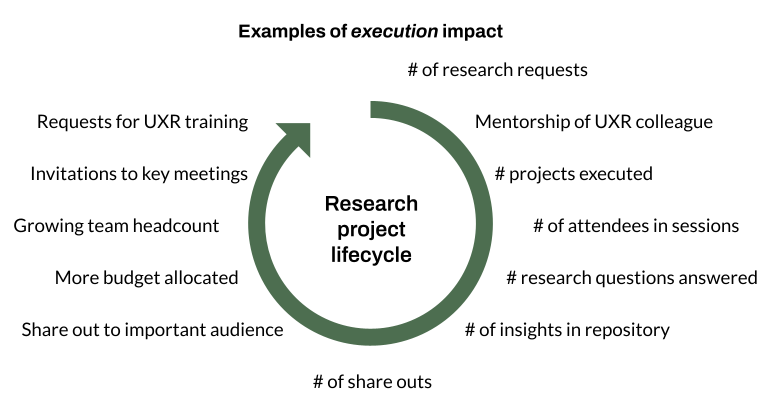

Execution impact exists where researchers begin, execute, and complete their project work. The locus of control is firmly within a researcher’s grasp, like projects completed, research readouts, or insights added in a repository.

Some external forces that are not in a researcher’s control are included here (research requests, invites to key meetings, etc.), but the locus of control is being handed to researchers to conduct their work. In this way, the control is with the researcher or being actively given (back) to a researcher.

There are certain impact examples that are also not strictly within a project a researcher is executing. Some are relevant to manager’s purview, like growing team headcount. Still, the headcount most directly functions to execute research projects. Another example outside of strict project execution is mentorship of a research colleague. This may not mean that a researcher executed a project, but that researcher unblocked or enabled another researcher to execute their project. These still fit into the execution component because they are part of the process of how research activities are being conducted (see note).

Execution impact is quite easy to measure. The elements are within a researcher’s own work processes. However, it’s generally of little importance to the business overall (I’ll talk more about this further down).

Influence

Influence impact exists when a researcher (or their work) causes another actor to change a decision or decide to do something they would not have otherwise. This is in the element of impact that most past frameworks agree on.4

Influence impact is the moment where researchers shift out of the locus of control related to their insights. A project readout is not influence (it’s execution) – readouts can be conducted with no decisions or changes made afterwards. We have to look at how stakeholder decisions or system changes occurred. This is often documented in something like a research roadmap, a Jira ticket for a fix in an existing product, or a citation in a strategy document for foundational/generative work. It could even be in less conventional places like a sales pitch deck or public company statement that the research enabled someone to make. Sometimes it’s not written down at all, but a researcher knows it informally.

This component of impact is important and prototypical for a researcher (considering the overlap in definitions of impact, and what I’ve seen on internal career ladders). It’s challenging because it’s partially outside of a researcher’s locus of control but it is the furthest end result that a researcher truly owns (in this sense that they are on the hook for it). For a parallel example, an increase of user growth isn’t entirely within a product manager’s locus of control, but they do own it.

It can be somewhat hard to track, especially if an organization doesn’t have a strong citation culture or researchers are not close with the team making the decisions. In moderately UX mature organizations, it’s not overly challenging to track. Businesses almost always care about influence as an impact of a researcher, because it’s the most prototypical impact for UX research.

Outcome

Outcome impact is removed from researcher control. The artifact, insight, or recommendation a researcher provided was taken by another actor in the influence phase, and that actor is measuring the success of their decision by some value. This measure could be a reduction in time-to-close support tickets, an increase in user growth rates, or an increase in revenue.

Some frameworks split up product metrics and business metrics, but these are similarly out of researcher control. Further, they are not universally more or less important – it depends on the business context (see a brief LinkedIn exchange with Dennis Meng5).

This impact is the hardest to measure. It takes place much later than the research project execution itself (Dong, 2021). Many other actors are typically involved in the process by the time outcome impact is known or measured. In contrast to the difficulty of measuring, it’s also the component of research impact that the business cares about the most.

Who cares about what kinds of impact?

As I’ve mentioned above, research impact is not universally valuable. I broadly consider two different types of people (dare I say personas?) that care about impact. They care about different parts of impact and use impact in different ways.

Type one: business importance

The type one person is someone in the business who owns an outcome related to their performance: revenue, user growth, time-to-close tickets, sales growth, etc. People make decisions with the goal to improve things, and research helps narrow down the decision options to those that are more likely to improve things. In other words, UX research is about de-risking and improving decisions. The type one person cares about how those decisions were made insofar as they can do the same thing again if they like the result (e.g.: use UX research when it worked well before). They don’t really care about how the decisions were made for their own sake. This is why execution impact isn’t valued widely.

The type one person can be not a person at all, but abstractly the shared goal of everyone at an organization. A public company cares the most about providing value for shareholders (sometimes this is through profit, other times growth). A private company cares the most about increasing profits (this could be debated and isn’t explicitly true for nonprofits, but that would be an entire article I’m not expert enough to write). In this way outcome impact is, at the highest levels of a business, the most important impact. Outcome impact aligns to any organization’s shared goal(s).

Outcome impact is the hardest impact to achieve and measure, because it’s outside of a researcher’s locus of control. This is by design: a researcher is brought into a company to operate far ahead of important metrics. If researchers could make an impact at the same time as the metrics, there would be no need for research at all. Because researchers are intentionally distant from metrics, a good organization (i.e.: UX mature) will place a big emphasis on influence metrics for a researcher’s performance review. This is the most crucial and prototypical point of contact between a researcher and the rest of the organization. Influence impact is what a researcher owns and is judged by directly.

As a final note, a typical researcher is also a type one person because they (a) care about the shared goal of the organization or (b) don’t want the company to go under and have to start interviewing for a new role.

Type two: personal importance

The type two person that cares about impact is you, if you’re a researcher, the person that wants to keep their researcher job or get promoted. A good performance review depends on understanding how you contribute to your team and your organization. The person you’re trying to convince is typically your manager, but could involve your skip-level manager or adjacent stakeholders. It all depends on how your organization works. Influence is often the main currency in these discussions, and outcome impact is a bonus, if you’re able to track it.

Execution is also something to care about as the researcher considering that it’s the input into subsequent types of impact. The number of studies run isn’t overly important: if you know what you’re doing it’s more about the quality of a study than the quantity. The only way I’d say it’s useful to index on the number of studies run is if you have no sense of what projects will land impact (most likely if you’re a very junior researcher). A manager’s view may disagree here when looking at coverage, but that’s a noted bias in the lens I bring.

Other instances of execution are a lagging indicator of good work and good will, like key meeting invites or requests for research. If you aren’t able to easily track influence, these can be good proxies for knowing research is being incorporated or used.

Impacts like research readouts can also be useful for calibrating your own work. If you see that certain kinds or venues of readouts with projects lead to more robust influence impact, it’s a strong sign to continue or expand those readouts in the future. Your boss’s boss may not care too much about the execution impact of readouts for their own sake, but it’ll help you be better at your job.

There is a lot to unpack here, so I am writing an in-depth post to dive even deeper. In quick summary: impact is tangibly a qualitative narrative you can use to keep your job, get promoted, or interview successfully for a new job. You need to align that narrative to who is listening. Influence impact is often the key type of impact you’ll reference.

Wrapping up

Writing about impact made me understand just how deep and fundamental it is to the practice of research. The initial post splintered into many posts, which are now linked throughout this post. My focus here was just to introduce the impact framework I work from as a bedrock for the other, more applied posts.

My framework of research impact includes three components: execution, influence, and outcome. I adopted a systems-thinking approach as much as possible to set these components in a framework that gives a reason for why they exist in contrast to other possible combinations or segments. While all of these components serve a purpose, influence is what researchers typically deal in most often and outcome is what businesses care about the most (when it can be tracked).

If you looked at the spreadsheet and have read the articles, it should be clear (due to the sheer variety) that an impact framework is a tool that must be bespoke to your personal context to be valuable. As a note on reflexivity, I’m an individual contributor (not a manager), I work in-house (not as a consultant). These things can probably help you decide how useful the framework is without any customization for your purposes.

I hope that this framework I have provided helps you understand what impact to focus on and why. I’m not guaranteeing it to be correct objectively, but let me know what value you do or don’t get from it.

Thanks for all of the authors for sharing their work publicly, it’s the best way our practice of UX research can grow. Thanks to Jeff Robertson for sharing his view on the way research ops may or may not think about impact, which helped me shape my thinking.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Sharon, 2012; Rebecca Destello, 2020; Sullivan, 2022; den Bouwmeester, 2024; Dombrowski & Whitman, 2024; Sosik, 2024; Vivas et al., 2024; Mattia, 2025 ↩︎

- Sharon, 2012; Rebecca Destello, 2020; Sullivan, 2022; Sosik, 2024; Vivas et al., 2024; Bach et al., 2024; Mattia, 2025; Liang, 2025 ↩︎

- Dombrowski & Whitman, 2024; Shukla, 2021 ↩︎

- Bach et al., 2024; Sullivan, 2022; Sosik, 2024, Vivas et al., 2024; Dombrowski & Whitman, 2024 ↩︎

- In this brief comment exchange, Dennis (CPO of UserInteviews) and I had a useful discussion about what impact matters most. While it’s easy to say money matters more than product metrics (my initial thought), Dennis observed (correctly, in my opinion) that many tech companies would value revenue growth or even indicators of it (user growth) over money saved. This is probably due to the speculative nature of tech investment and how the stock market functions as a whole. Other industries would likely value types of metric changes differently. The main point here is that it’s highly context dependent which metrics are most important. ↩︎

Tables and images

Citations

Note: all frameworks I cited are footnoted or formally cited (APA) for clarity. Links not in the framework that are only referred to once are simply hyperlinked.

| Author | Name | Link | Cited as |

| Tomer Sharon | Signs UX research is making an impact | https://www.uxmatters.com/mt/archives/2012/05/signs-ux-research-is-making-an-impact.php | Sharon, 2012 |

| Rebecca Destello | Defining research impactd | https://design.facebook.com/stories/defining-research-impact/ | Rebecca Destello, 2020 |

| Tao Dong | Three levels of UX Research impact | https://uxdesign.cc/three-levels-of-ux-research-impact-174768b7f4ef | Dong, 2021 |

| Kanishk Shukla | Tracking impact of day-to-day UX Research activities | https://medium.com/alaskaair-guestdigitaldesign/capturing-impact-of-day-to-day-ux-research-activities-on-teams-part-1-891a5c25c45f | Shukla, 2021 |

| Caitlin Sullivan | Tracking the impact of UX Research: a framework | https://uxdesign.cc/tracking-the-impact-of-ux-research-a-framework-9e8b8f51599b | Sullivan, 2022 |

| Dr. Paula Bach, Safiya Bhojawala, Dr. Melissa Boone, Kara Costa, Dr. Hilary Dwyer, Dr. Theresa Horstman, Dr. Alexis Neigel, & Dr. Alaina Talboy | Between Two Bookends: Making and Measuring UX Research Impact | https://medium.com/uxr-microsoft/between-two-bookends-making-and-measuring-ux-research-impact-8978b7787c36 | Bach et al., 2024 |

| Karin den Bouwmeester | Multi-level framework or UX research impact | https://uxinsight.org/how-to-measure-ux-research-impact-a-multi-level-framework/ https://www.linkedin.com/posts/karindenbouwmeester_uxresearch-impact-uxstrategy-activity-7326191047074537473-4Ukz | den Bouwmeester, 2023 den Bouwmeester, 2025 |

| Roberta Dombrowski, Lorelei Whitman | Defining research success: A framework to measure UX research impact | https://maze.co/blog/ux-research-impact/ | Dombrowski & Whitman, 2024 |

| Josh LaMar | The Impact Problem | https://uxdesign.cc/the-impact-problem-950a707f2bb3 | LaMar, 2024 |

| Ruby Pryor | Untitled post | https://www.linkedin.com/posts/ruby-pryor_design-uxresearch-uxr-activity-7110155624004427776-_ubI/ | Pryor, 2024 |

| Sprig, Victoria Sosik (cited) | A Framework for Measuring Research Impact | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y-Q5IcFHlgk | Sosik, 2024 |

| Victoria Vivas, Maria Hock, Ezequiel Djeredjian | UX Research Team metrics | https://medium.com/@decoding.research/ux-research-team-metrics-c7595698e3b7 | Vivas et al., 2024 |

| Julia Della Mattia | Let’s Discuss Impact as a UX Researcher | https://finderstobuilders.substack.com/p/measuring-impact-as-a-ux-researcher | Mattia, 2025 |

| Kevin Liang | From UX Insights to IMPACT – Measuring UXR Success | Crash Course pt 4 | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EXddn2hFF_8&t=582s | Liang, 2025 |

Axes related to the framework

| Impact framework components | Execution | Influence | Outcomes |

| Importance to business | Low | Medium | High |

| Temporal order of activities | Beginning | Middle | End |

| Locus of control | Researcher | Researcher to Stakeholder | Stakeholder |

| Ease to measure | High | Medium | Low |

Execution cycle

I’m risking adding another figure for another framework, but here it is anyway. All of the execution examples don’t all fit perfectly in a lifecycle of a single project, but it can help to think about how these items grow and build on each other in a cycle of successful project work. Success in this case would fall upon the later types of impact (influence, outcome) feeding back into more execution potential when well-documented and known.

Image credits

All icons from flaticon.com.

Images generated with Gemini.