TL;DR – outcome impact is most important to an organization, but the hardest for researchers to track. There are some cases where researchers can improve, but in certain situations researchers cannot track outcome impact so they must focus on influence impact.

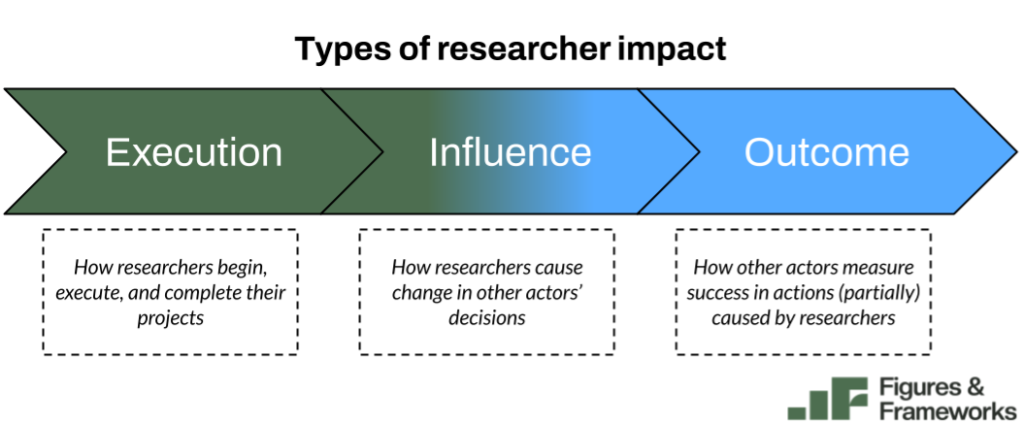

In my framework for research impact, impact includes the research process and how its results drive decisions and affect stakeholder outcomes. It has three components, execution, influence, and outcome. Influence is the most prototypical kind of research impact — it’s also the final step the researchers truly own. Outcome impact is how others measure success based on decisions that were influenced by UX researchers. Even though influence impact is most prototypical, outcome impact is the most important impact to a business.

There have been lots of discussions in the past few years about how UX research isn’t focused on the business enough — we aren’t driving outcome impact effectively1.

I disagree that lack of outcome (business/product) impact tracking is truly a problem for UX research, in most cases.

UX research’s impact on outcomes is a nice-to-have — it’s not crucial for UX researchers to have at the end of every project. Outcome impact is not essential, but nice-to-have, because:

- UX research is deliberately far from outcome metrics.

- UX research deals in counterfactuals and hypotheticals.

- Communication and visibility deteriorates over time.

- Impact diffuses over time.

I’ll go over these four reasons in detail, and which of them we can fix (#3 and #4).

Josh LaMar also wrote about this topic of measuring outcome impact in his framework, so go read his article too if you want a related perspective.

Why outcome impact is hard to measure

#1: UX research is deliberately far from outcome metrics

Why do organizations hire a UX researcher? Whether the stated goal is understanding users better, improving the user experience, reducing friction, improving revenue, etc., the common thread is de-risking decisions of stakeholders.

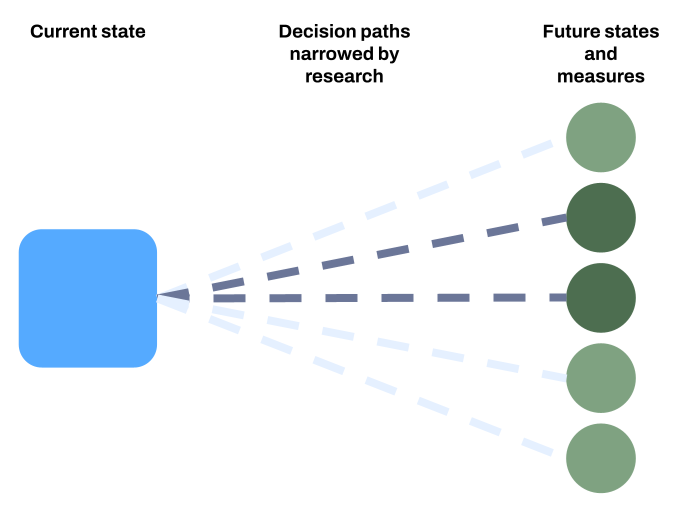

In any product context, there are many ways to move forward in an initiative. Each of these outcomes is uncertain in how effectively they’ll meet the team’s goal. Eventually, one path is chosen and the goal is measured. The team then sees: did we meet our goal? By then, the team knows if they’re successful, but it’s too late if they failed: the resources have already been spent.

Even with just two ways to move forward, it can be quite costly for a team to spend time and resources implementing one way to find out the decision didn’t help them to meet their goals. Research (that is rigorous) effectively narrows down these decision paths into those that are most likely to help the team reach a future state that meets their goal.

Research is, ideally, far upstream from the point of measurement in the future state. The further upstream, the more poor quality decision paths can be avoided. In a hypothetical world, what if research happened at the same time as metrics? The decision would be made, the metric would be measured – there would be no need for research!

This upstream position of research in the flow of product development is tied to the purpose of UX research. UX research provides an estimation of a future state given a certain decision path because we can’t measure the future state yet. This temporal distance from future states makes it hard to measure the final team goal in connection to the initial research (see #3 and #4 as to why), but that distance is intrinsic to the value of research.

#2: UX research deals in counterfactuals and hypotheticals

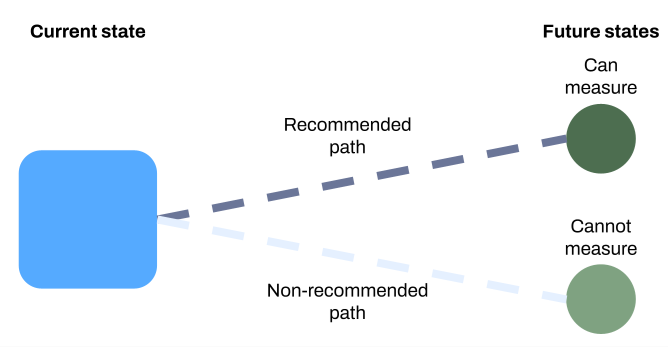

UX research insights typically lead to a recommendation, most often to do something. There are also valuable moments where a research insight will lead to the opposite conclusion: don’t do something. We’ll call this a negative recommendation. Assuming that the research is all rigorous, both positive and negative recommendations can be equally valuable for the team. The latter is in the realm of counterfactual outcomes.

In product testing and data science, teams use A/B tests to just do both things and avoid dealing with counterfactual outcomes (often because a default or control state is already built). When it can’t be avoided in data science, there is even a domain of analysis dedicated to counterfactual analysis. UX research insights typically don’t allow for this. If a negative recommendation says to not build a new feature, the team will not build the feature to A/B test it.

This means that negative recommendations, which are valuable to teams and count as influence impact, do not allow for outcome impact to be measured. The alternatives (building the sub-optimal feature to test it or avoiding negative recommendations all together) don’t make sense. Therefore, some great UX research cannot have outcome impact that is measurable.

Side note: this concept of counterfactual outcomes really applies to all UX research. Let’s say UX research recommends the team builds concept C over A and B. Even if concept C shows a 100% increase in the team’s metric when launched, we don’t really know A and B wouldn’t have shown 200% increases. This is why rigor is so important (post coming soon), it is our best tool to ensure that C was the best option given the impossibility of counterfactual measures.

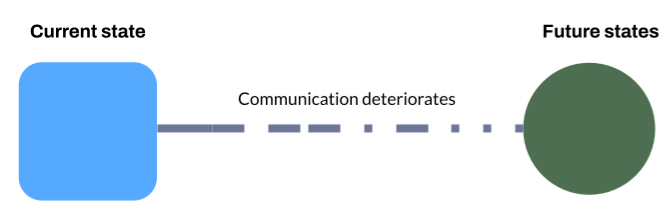

#3: Communication and visibility deteriorates over time

When a researcher has any kind of influence impact, they give over control of their insights and recommendations to other stakeholders. At that point, the researcher no longer owns the actions based on the insights. A researcher hopes these actions lead to outcome impact, but it isn’t fully their domain. Further, a researcher cannot wait around for the outcome impact. The researcher needs to jump into their next project to produce more insights.

Let’s say a researcher gave a recommendation that is prioritized by the team (and it’s not a negative recommendation). The researcher then goes to work on their next project. During that time, the designer and PM need to interpret the insight, the engineer must implement the designs correctly, and a data scientist must set the logs up to properly measure the impact2. This happens over weeks or quarters across scores of meetings and periods of work. The researcher may be in some of these meetings if they’re embedded, but sometimes none at all. All the while, a researcher cannot easily focus on this thread of work because they’re producing new insights.

To track down final outcome metrics, a researcher would have to know how the team’s initiative is being measured in an instance. They would also have to find their way into meetings they may not know of or be invited to. It’s a major effort for researchers to keep track of how their decisions were used and ultimately implemented. When a researcher is busy conducting other research work, the payoff to take time and effort to learn about the outcomes is not necessarily clear.

Ultimately, researchers are not paid to see how their work affected final outcomes, they are paid to produce high quality, novel insights for teams to use in the decisions.

#4: Impact diffuses over time

In addition to how it can be hard to know what happens in final outcomes, it’s also true that a researcher plays a small role in the final outcome impact related to their insight. This is in contrast to influence impact: a researcher does the work and directly advocates with stakeholders for change, which is agreed to or not.

A researcher, especially in foundational or generative projects, plays a massive initial role in shaping product offerings or organizational footprint/directions3. In exceptional foundational work, a researcher could provide the broad direction that no one in the entire organization was aware of (let alone considering). When the researcher advocates for those foundational insights in an exceptional way, the researcher could plant the seed that causes a shift in the entire team towards their recommended direction.

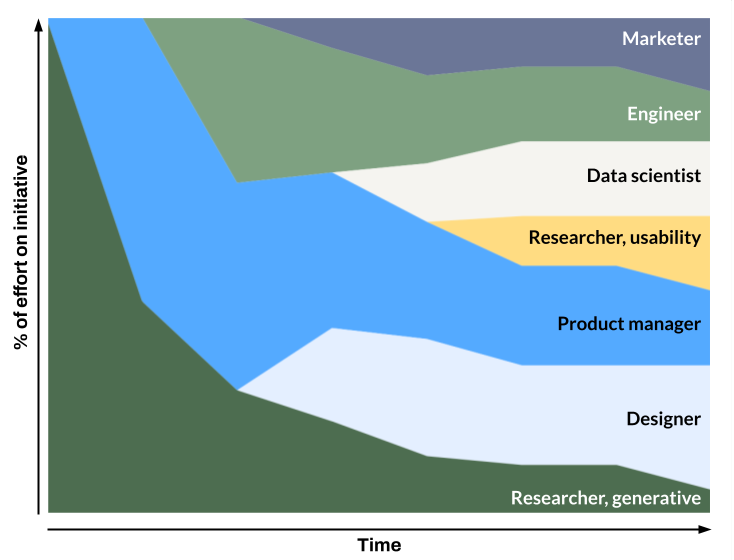

Once this shift has taken place, more and more hands are involved that see it to fruition. Product managers will align other functions, designers and engineers will build the product, marketers will develop plans for go-to-market, data scientists will develop metrics and measure outcomes4. At the final stage of a project, a generative researcher may be barely involved in the work they fundamentally allowed to begin. This makes it difficult to consider what share of the impact a researcher is owed at that point5.

It can be easier in a usability space where a feature already exists and the scope is quite narrow. Even then, many other hands were involved in the feature before the research began, also making it difficult to conceptualize the researcher’s share of the impact.

Researchers, I think, are highly collaborative by nature of the discipline. A quick web search will show you that “UX research is a team sport”. This can lead to a humbleness in claiming outcome impact in metrics related to big projects. In my experience from talking with other researchers, many researchers wonder if they are “allowed” to claim impact in these cases.

What can UX researchers do about it?

There are four major forces working against UX researchers from finding outcome impact, the most important impact to a business or organization. What should researchers do about it? In some cases, there is nothing to do, because it’s part of the nature of research.

We can’t change #1: research is by design far from outcome impact and its measures. Changing this system would mean that research is no longer needed, because we would already know the outcome.

Similarly, we can’t change #2: research deals in counterfactuals and hypotheticals. This is also by design. We do research to avoid developing multiple features or initiatives. Building out those sub-optimal initiatives to test them would also mean there is no point to research, as it’s not saving effort or reducing risk.

There are some things researchers can do to more effectively track outcome impact.

What we can change

Researchers can get better at #3: there are tools and processes we can adapt to reduce miscommunications and lack of visibility. Some of this is context dependent – a researcher that is deeply embedded will naturally be in more meetings and communications. A researcher that works across pillars or is in an internal consultancy model may not have the same ease of communication. In either case, similar ways to stop this communication deterioration apply:

- Get access to the outcome information.

- Spend some upfront time with your teams learning how and where they measure outcome impact. Figure out the typical cadence. This takes effort, but it should be easier to track outcome impact once you know where it is. Set up one-on-one meetings or take some time in existing meetings to discuss it.

- Be direct and just ask stakeholders, “Remember when we did X that was influenced by Y research project, how did the metrics look when we launched?”. It feels a bit odd to do, but I haven’t received any awkward responses when I’ve asked something along these lines.

- Take notes of what happened.

- Once you know where the impact takes place, you have to keep track of it. I use a simple spreadsheet that strings together all types of impact within a single research effort. Once you’re in a habit of putting a quick note or screenshot in your tracker, it becomes second nature. A bonus here is that you can sense trends of where and how outcome impact is best measured or achieved.

- Build a citation/credit culture.

- This is a hard one, but it can be done over time (I’ve been in places with more and less success). If teams are used to citing research and informing researchers about the citations, then you’re more aware of where your work is and what happens with it. I wouldn’t call this a tactical move, but something you invest many quarters into building with your team and stakeholders.

Lastly, I would say #4 is even easier than #3: even if your impact is diffuse, claim it! Impact is all about narrative. If you can say how you influenced a team to do something differently, then you can build a narrative that leads to you claiming some impact in the end.

Like I said before, researchers have a “team sport” mindset. In a team, the whole team wins, not just the star player. From researchers I’ve talked to, it seems they are waiting for permission to claim impact even when many others were involved in the effort. Well, for what it’s worth, I am giving you permission right now. Even if your attempt doesn’t land with a manager or stakeholder, consider what you can tweak in the impact narrative, not if you deserve the impact in the first place.

Outcome impact is nice-to-have

In the business world, it would be great to always link research work with the metrics businesses care about most. As researchers, we can get better at tracking metrics (when possible) and claiming more credit of ours, where it is due. But also, not only is tracking outcome impact challenging in many cases, it’s also impossible in cases of counterfactual decisions or features.

I believe that a sign of a company with a matured viewpoint of research understands the relationship of research to outcome impact and indexes more heavily on influence impact6. Influence impact may not matter as much to a business as outcome impact, but it’s the final result that researchers truly own. Most research teams are stretched thin, and we don’t want to become mired in fact-finding missions for metrics we don’t own.

In the big picture, outcome impact is still the most critical for anyone in an organization. We should seek it out when we can as researchers and have a strong awareness of how our team or organization is doing, even if we can’t directly measure it. The best way to contribute to outcome impact as researchers is finding the appropriate level of rigor, not solely by tracking outcome impact (more on this soon!).

Appendix

- See my previous post’s discussion. ↩︎

- Again, Josh LaMar lays out this process in greater detail than I will here. ↩︎

- Dave Hora lays out a helpful framework for considering scale of strategy, and uses these terms. ↩︎

- This isn’t a canonical view of who is involved with projects when, just an example for illustration. You could easily see differences in an industry project, like a DS involved early to help validate generative research. ↩︎

- Share of ownership sounds harsh and formulaic, but some places (like Meta, from my experience) do strongly consider this as a factor in impact for performance reviews. Looking at one source from Meta I used for my impact framework, this could be why the Meta researchers did not consider outcome impact to be a type of researcher impact – they’re not allowed to claim it! ↩︎

- How can an organization know if research is really leading them in the right direction without outcome impact? Well, we know that ask is impossible in some cases, so it’s best to have a plan that addresses this. I’ll post another article soon to discuss this: rigor is the only path to ensuring the business gets what it wants from research (business != your nearest product manager). ↩︎