Rigor gets discussed quite often in UX research. It’s normally invoked during the discussion of how fast UX research should move or how UX research differs from academic research. I don’t want to weigh in on the question of balancing rigor and speed here (but I will). I want to back up and consider, what exactly do we mean by rigor in UX research?

I found some past definitions and discussions of rigor in UX research. Ward and Polgár defined it primarily through a qualitative lens (based on Lincoln & Guba). In contrast, Engkvist defined it primarily in quantitative terms (broadly a psychometric approach, though not cited to an original author in the post). Others have written about rigor in its application, without a focus on defining it (Moss, Anderson-Stanier, Utesch).

I want to define rigor in UX research comprehensively. My intent is also that this definition will elucidate discussions of more applied questions like balancing rigor and speed.

First, some philosophy

UX research is, descriptively, a mixed-methods domain – researchers typically employ qualitative and quantitative methods. Therefore, rigor in UX research must inherit definitions from both qualitative and quantitative paradigms.

Each paradigm emerged from differing (and sometimes opposed) philosophical traditions, interpretivist1 and positivist, respectively. Interpretivism is qualitative, focused on understanding subjective meaning in context. Positivism is quantitative, focused on objectively measurable data that is generalizable.

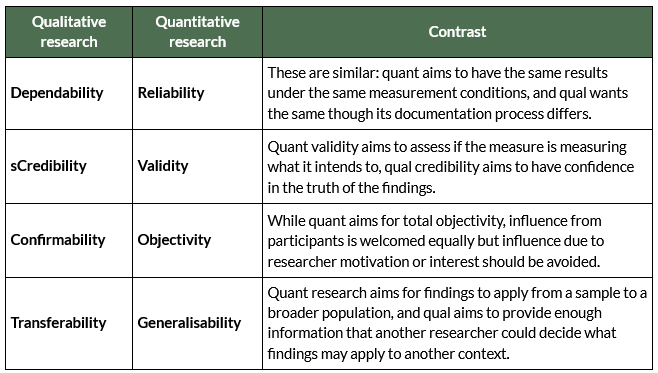

Despite the differences, there is some alignment in how each paradigm ensures rigor:

How do we merge the traditions of rigor for UX research when the philosophical foundations are different across qualitative and quantitative methods?

There is an academically-rooted research tradition called action research, a philosophy of social science methods that links research with applied goals. UX research has an obvious throughline with Action Research due to its applied nature.

Action research already merges qualitative and quantitative paradigms to meet its practitioners’ goals. You might have read a bit about explanatory sequential, exploratory sequential, convergent parallel designs, or even quasi-experimental designs. These are examples of mixed-methods, action research designs.

One flavor of action research is particularly useful for UX researchers, Chris Argyris’s action science. He posited that in the action research paradigm humans design their actions to achieve intended consequences and are governed by a set of environmental variables2. Research is part of the design-of-action process where we set out to learn about environmental variables to achieve our intended consequences.

Defining rigor

UX research is an implementation of these Action Research philosophies (often in the context of a product or service). So then what is rigor, considering that UX research is an implementation of action research? Rigor in UX research is when environmental variables are effectively uncovered to help shape decisions that lead to intended consequences.

Rigor in UX research is when environmental variables are effectively uncovered to help shape decisions that lead to intended consequences.

While the truth may not fully exist in an action research context that draws from interpretivist traditions, research does aim to get to a truth that leads to decisions with desirable outcomes.

We can think of rigor as a process of achieving clarity — rigor helps us wipe our lens so we can more clearly view a useful reality in which we need to make decisions for our organization. When the lens is blurry, we may reach for the wrong thing or take the wrong path. When we clear the lens, we know what we’re reaching for or moving towards, enabling us to better understand if that choice will lead us to the outcome we desire.

The way rigor is achieved hinges on the type of research (qualitative vs. qualitative) and uses the concepts I showed in the table above3. In either case, the goal is to make our decisions more likely to lead to the outcomes we want.

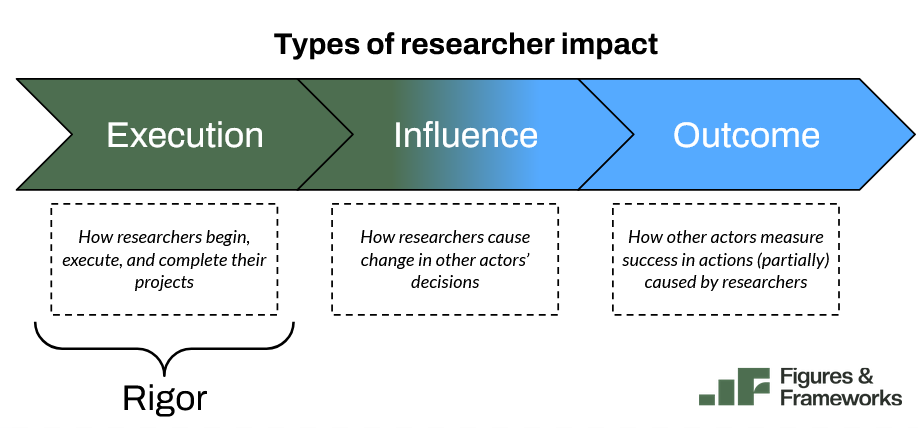

Fitting into the bigger context

How does rigor relate to impact? Calling back to my framework for research impact, creating rigor is entirely contained within the execution impact of research. It’s traditionally thought of as how a study is designed and analyzed. Another aspect of execution is the sharing of research4. Rigor matters here too in how faithfully we present our findings (think truncated in Y axes on bar graphs or not presenting counter-evidence from interviews). I’d liken rigor to craft in UX design: it’s the foundation of an IC’s work. This isn’t to say influence is less important, far from it, but influence needs to stand on rigorous execution.

Organizations don’t care about rigor directly (because they don’t care about research execution), they care about outcomes. And they want those outcomes to be positive! Rigorous research execution helps achieve positive outcome impact5 by clarifying the view of reality related to an organization’s decisions.

Influence is orthogonal here, your influence can be based on non-rigorous findings. In this case, you risk making a team sprint in the wrong direction, and the whole point of UX research is to de-risk!

The importance of rigor

There is more to research than rigor alone. Researchers must be effective sales people for ideas and navigate human politics. Much of senior research work is not primarily concerned with rigor, but how to generate actionable research questions and ensure coherent action. However, rigor is what all of the other critical researcher tasks stand upon.

To be a UX research practitioner, rigor is the ticket to entry. It gets you in the door because it’s foundational to a high quality UX research process. It doesn’t mean the job stops there — quite the opposite, as many find out when moving from academia (which focuses primarily on rigor) to industry (which focuses primarily on action). When the foundation of rigor is not set, the action is all for show and leads to bad outcomes.

Learning to be rigorous

If you want to learn more about rigor, the only way to do this is to deeply understand both qualitative methods and quantitative methods for their own value and systematic approaches. I don’t have any shortcuts, but I also won’t prescribe a single path.

I learned my foundational knowledge in my graduate program (in human factors psychology) . The methods courses I took focused on reviewing existing research papers and then critiquing those papers. The best classes also focused on what findings we could still take from flawed papers, despite the issues (this helped to learn when/how to cut corners the right way). At the end of a typical course, I’d write my own research plan and have it critiqued/graded. Throughout these processes, we had extensive discussions, going back and forth about the merits and flaws of what we saw or wrote.

I continue to learn learn about rigor by seeking out best practices from credible practitioners and working to update best practices in the methods I use (using peer-review when pragmatic). The skills I found in grad school didn’t stop being used after school was done.

You don’t have to go to grad school to learn rigor, but that setting does one thing I think is important to replicate, even if you read all the textbooks and papers you can find on your own: peer discussion facilitated by experts. If you’re taking a self-study approach (see my quant guide here), be sure to connect consistently with peers and mentors. Be curious for feedback and challenge each others’ ideas. This discourse is how you can sharpen your skills beyond the text on the page.

Wrapping up

Rigor in UX research draws from qualitative and quantitative philosophies of science. We merge these definitions by considering what we value in UX research: how it affects our organization’s outcomes. One more time, the definition I’m proposing for rigor in UX research is when environmental variables are effectively uncovered to help shape decisions that lead to intended consequences.

Rigor is crucial for UX research as a field. It’s how we ensure our findings positively impact our organization’s goals (the most important impact to our stakeholders). Lots of discussions around speed and democratization are taking place in the UX research discourse, and rigor is at the center of those. I hope this definition of rigor can help shape these conversations for the better.

Appendix

- Really there is more than one qualitative philosophy of science, but I’m simplifying a bit. ↩︎

- The premise of action science, Chris Argyris’s theoretical approach to action science, gives that the purpose of action research is “generate knowledge that is useful, valid, descriptive of the world, and informative of how we might change it.” Further, “knowledge that can be used to produce action, while at the same time contributing to a theory of action.” ↩︎

- This table shows how to positively approach rigor. I also find threats to validity a useful framework to see how rigor is deteriorated. This page sums up threats to validity from classic sources, if you want a quick overview. ↩︎

- Ward says this is some way. “Rigor is also external—research rigor is a way to establish confidence and trust in research findings. In other words, it’s not just about how rigorous the research is but how stakeholders perceive its credibility. In academia, that’s research peers, but in UX research, it’s the non-research stakeholders with whom we regularly collaborate.” But I think it has less to do with the credibility it’s given and more about how faithfully we share our findings. Liu agrees, I think, saying “Rigor in how we design research alone isn’t enough — we need to be rigorous in how we interpret research findings as well. Doing both is part of the job, and it’s how we create good research.” ↩︎

- Even though there are situations where we cannot measure outcomes from research in an organization, we can apply the same principles of rigor from when we are able to measure outcomes, proving the general value of rigor. ↩︎